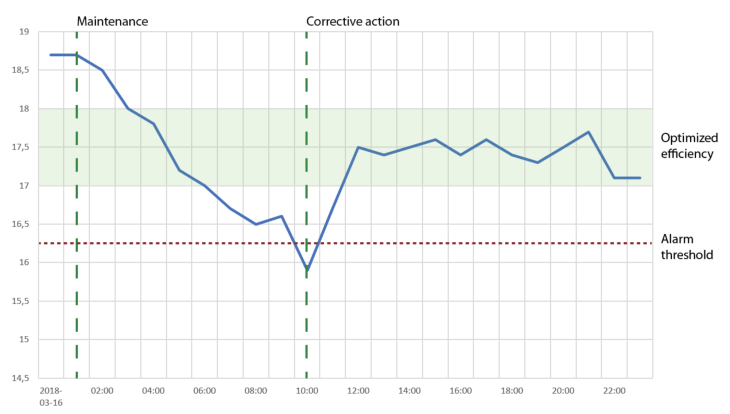

Over the years, the most common requirement for a dashboard I encounter is that we need a simple view for the upper management. They don’t have time to dive into details and in it’s most simplistic form they want to have a traffic light view, telling them all is good or not. In this post, I will discuss the difficulties we face when trying to make such a dashboard and why it will be a bad choice if the dashboard will be used for making decisions in the next phase.

The traffic light

Traffic light (By Unisouth – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3934535)

The traffic light is a well working concept. For it’s domain, controlling traffic, it’s easy to understand and universal. Crossing a street as a pedestrian is a binary decision – you either wait or go. Same when driving a car – it’s either your turn to drive or you should be standing still letting other traffic go. It’s probably one of the most effective decision support tools we have for damage prevention.

What is easy to forget is that a traffic light is not the only sensory input you have when crossing streets. If you are a pedestrian, you eyes and ears will pick up signals that can tell you not to fully trust the traffic light. Like, an ambulance might be crossing at high speed. On it’s own, a traffic light can be a dangerous single source for decisions, and it should be augmented with other inputs.

What managers want

Of course there are no single right answer to what managers want. We are often told that time will be a significant constraint, and from there the conclusion will be that they need a dashboard with few elements, and the one with the least elements we know is the traffic light. My first argument is that managers want to have a good view of the organization status. The more knowledge they have, the better the data driven decisions will be in most cases. The traffic light, even though it will take micro seconds to understand, will not give enough detailed insights.

My other argument is that there are less correlation between the number of elements in a dashboard and the time needed to interpret the information than most think, as it will depend on how elements are presented. To it’s extreme, I can argue that having hundreds of elements will in fact be good, which we will see later.

Key performance indicators

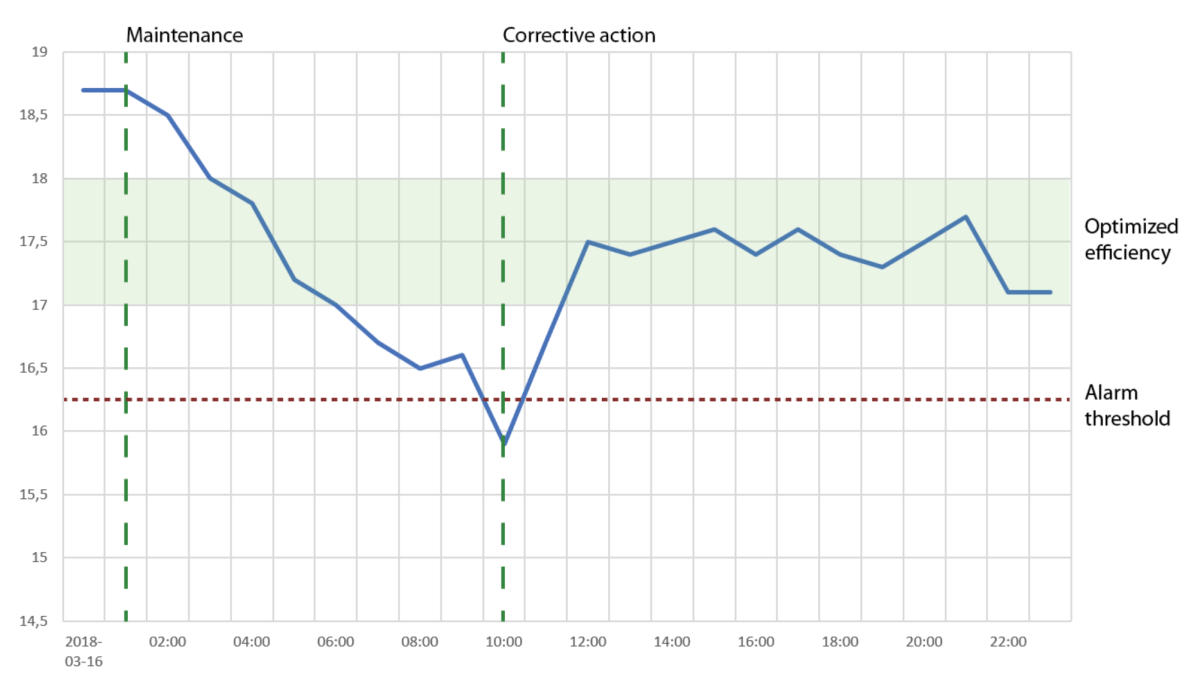

A dashboard could benefit from having some kind of interactive drill-down or more details when a user reads from the top of screen to the bottom. Often key performance indicators (KPIs) are used in headers, and it’s these KPIs that also give the data for the traffic light constructions. The challenge will then be to

- Determine what will be good KPIs

- Determine the visualization of the KPIs

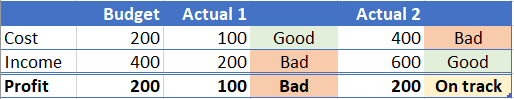

As an example, we can say that we want a sales dashboard. Sales will have a budget, a cost, and an income, and we want to track current year to previous years and budget. Managers are often involved in setting budgets, so a report will typically be to say that you are on the budget or not – i.e. a binary decision and then we think it’s a good idea to have a traffic light, right? A budget is usually an estimation of cost and income, thus profit, to come. So what does it mean that you are on the budget – you have a cost that is comparable to budget, you have an income that’s comparable, or you compare the profit? Are you comparing the values directly or some percentage or other calculation?

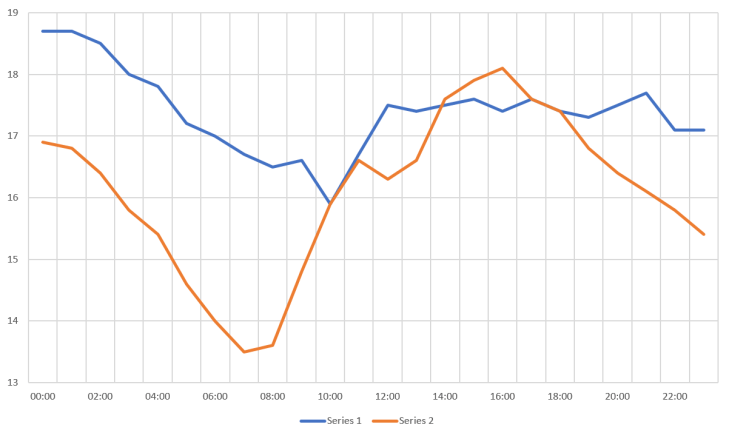

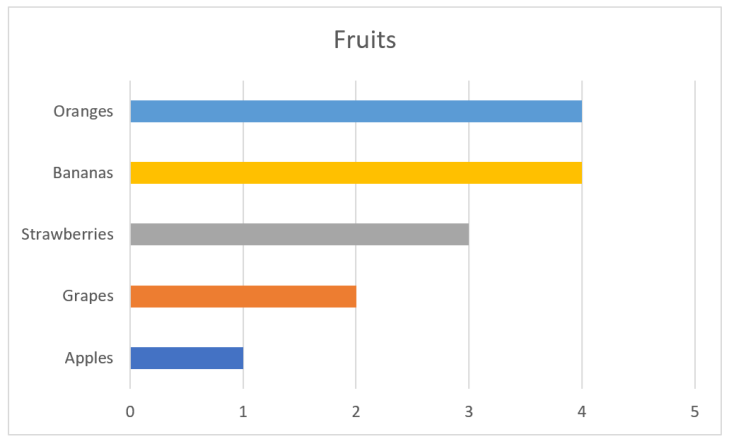

Actual vs budget

The example in the table shows one budget and two actual situations. The first shows that you are not spending over budget, but you are not making so much money either, so in value the profit is below budget. In percentage, you still earn twice as much as the cost, so if this was the metric it would have been on track. The second example has some overspending, but the income is above budget and profit is where it should be according to budget. For our traffic light dashboard, it will not be obvious how we should code the different scenarios, as both could be fine or bad.

Problem arises however, when a traffic light dashboard is presented for managers. Let’s say we base a KPI on new profit. First scenario gives then a bad indicator, and then the managers will of course question why things have gone bad. In the second scenario, you tell them everything is fine, even though you have doubled the costs, for which managers probably should have been informed. It’s easy to see that traffic lights do a good job of hiding information and rising more questions than answers. An easy fix would be adding more traffic lights – one for each parameter, as more or less have in the table. Then it’s easier to see the cause of good or bad profit. Also, including numbers for budget and actual will give additional information for how good or bad the situation is. Thus, having more elements in a dashboard is actually a good thing.

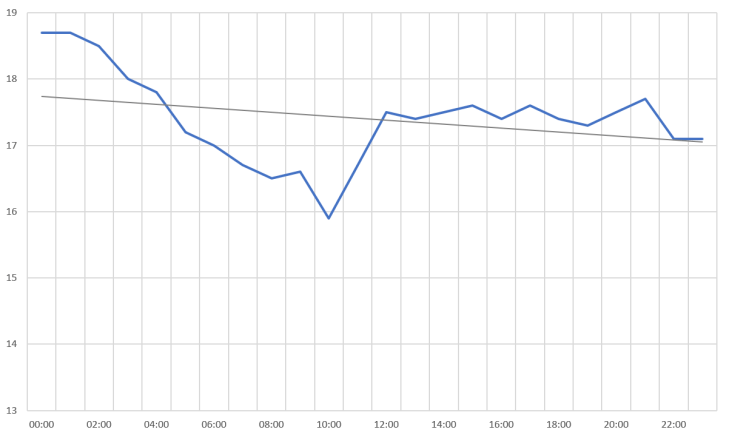

Using statistics

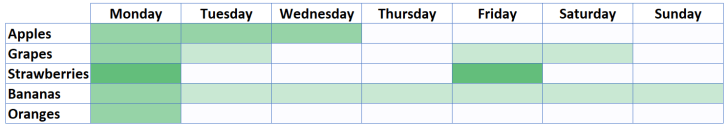

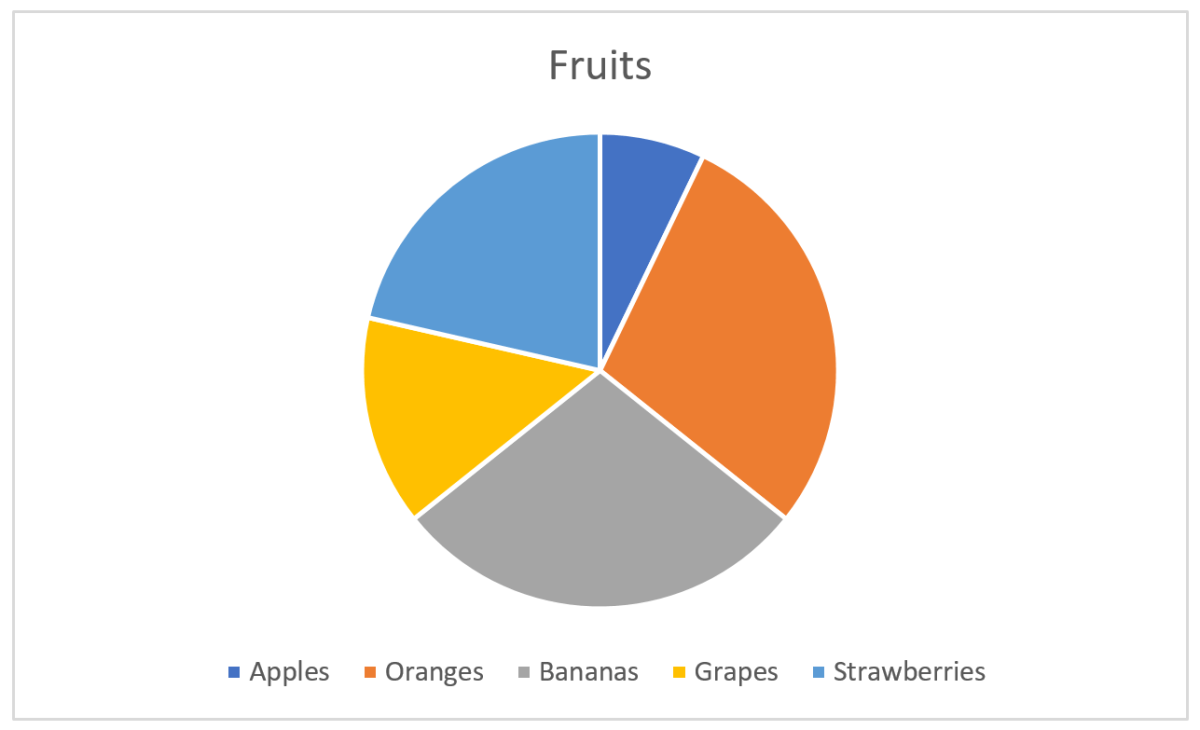

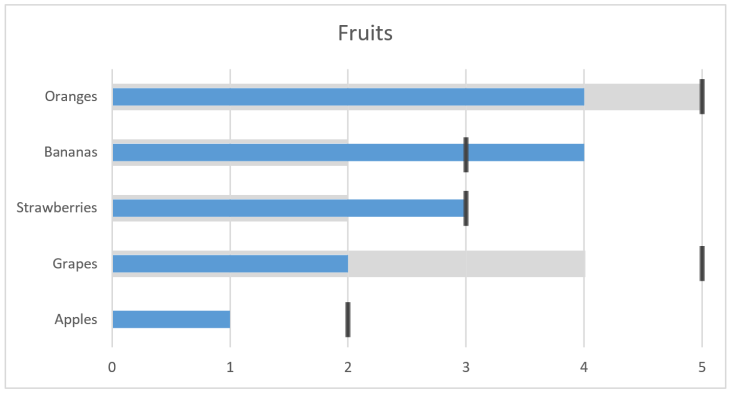

Since this post is about taking intelligent decisions based on data, a cautionary note should also be said about using averages. Average is commonly used as a KPI, so it is important to know what it actually represents, and not represents. The average is calculated for a set of values and it is an indication of the distribution of the values. As an example, let’s assume we are selling fruits across Europe and our KPI is based on the percentage change from 2018 to 2019 (this is by purpose as percentage will give large values if the initial was very low, e.g. if we go from 100 to 110 this is an increase by 10%, but if we go from 10 to 20, same amount as before, this is 100% increase).

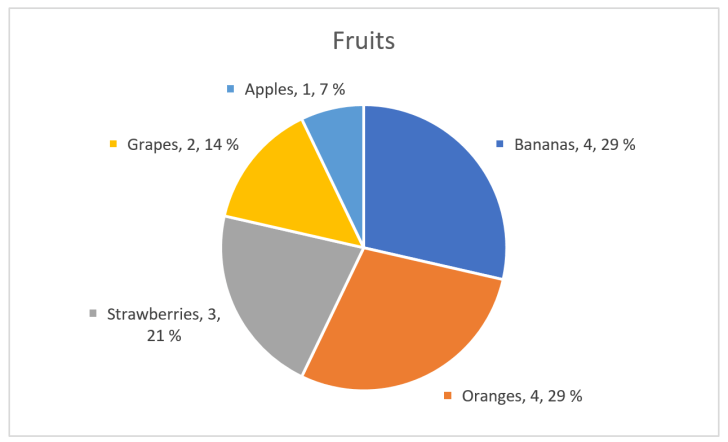

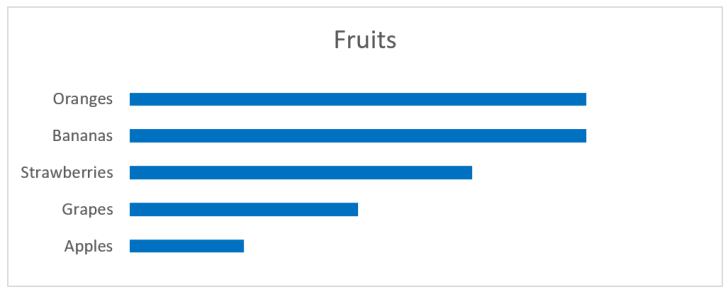

Averages (showing a subset of the values)

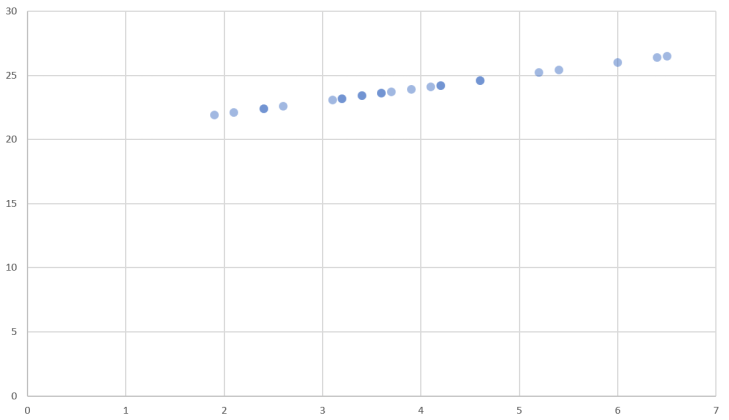

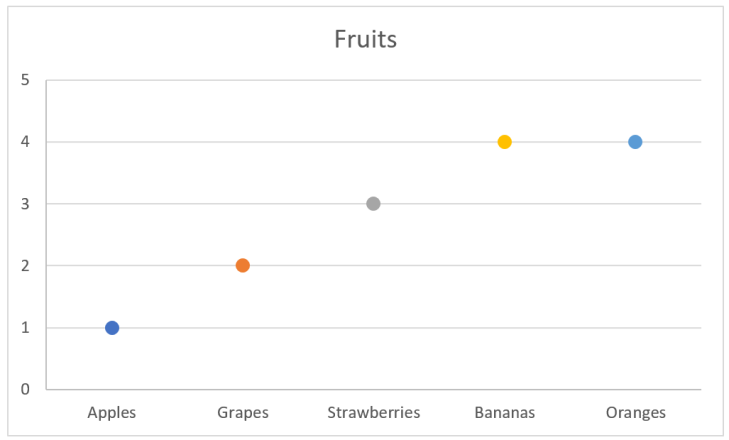

On average we are 173% up. Not bad at all and managers can be very happy! Actually, a lot of countries have gone down, but we have a couple outliers with very high percentages. The average of percentage says we have more than doubled, but the average absolute value is in fact very small (2.3). We still want percentage to be our KPI, so the problem is the use of average. Let’s look at a distribution by just plugging the values into Excel’s histogram:

Percentage distribution

Immediately it should be clear that the outliers are causing the average to be complete off with regards to what we actually want. Data that is unevenly distributed should not use average, as average more or less requires a normal distribution. Too bad that average is so commonly used in our language that we use it without considering the consequences. A better statistical function would be the median. This is basically sorting the values and picking the one in the middle. For our percentages, this would give a number close to 0%.

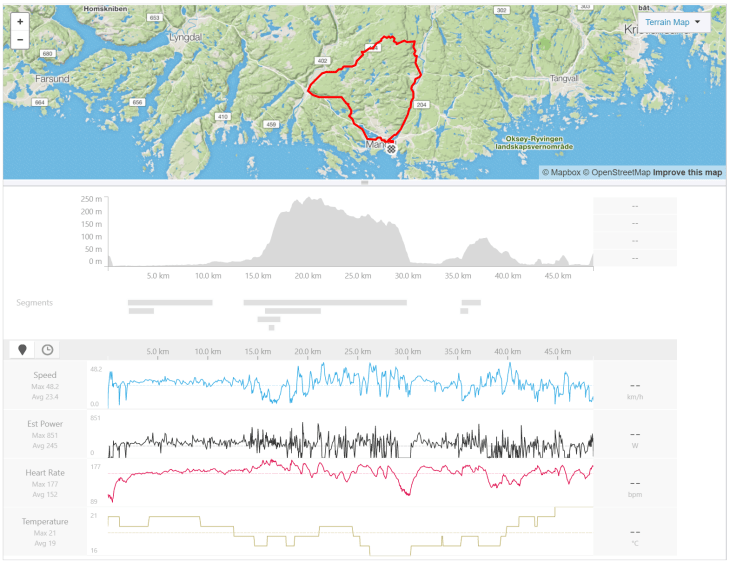

Intelligent decisions

In order to make intelligent decisions, managers should be presented with KPIs and explanations for those data. For our sales example, a bad profit over a year could be augmented with e.g. monthly values (or deviations from budget). There one can see that the first quarter was hard, but the rest of the year showed a positive trend, i.e. keep on doing the same thing. Or that even we are on budget, the last couple months had a negative trend so additional actions could be necessary. In Excel, you can add sparklines. In addition, showing tabular data, maybe color code values to show good and bad, is in fact easy to understand. Thus, I believe one can show a large number of values, together with explanatory charts like a sparkline, and have a dashboard that will give much more intelligent decisions than a traffic light.